Unease Over New Zealand Overtures to US in Pacific

New security-state documents show Wellington aligning its military with the “rules-based international order” while preparing Kiwis for war with key trading partner China.

This story first appeared in Consortium News on August 28, 2023

Reports from New Zealand’s security state have sparked protest after all but suggesting the country join the US-led AUKUS military alliance, a move that would reverse years of New Zealand’s independent foreign and defence policy and put it on a collision course with China.

Ex-Labour Prime Minister Helen Clark lamented the loss of what would remain of the country’s military sovereignty, pointing to an “orchestrated campaign” by defence and security officials to join the U.S., Britain and Australia in AUKUS.

In a Twitter thread, she said the government was “abandoning its capacity to think for itself and is instead cutting & pasting from Five Eyes partners” and called for a public debate on the issue. New Zealand is part of a five-nation intelligence sharing arrangement with Australia, Britain, Canada and the United States.

Clark tweeted that “there appears to be an orchestrated campaign on joining the so-called ‘Pillar 2’ of #AUKUS which is a new defence grouping in the Anglosphere with hard power based on nuclear weapons.”

The former prime minister quoted from an op-ed article in The Post on June 4 by academic Robert G Patman, who wrote that “Aukus has already been criticised for fuelling nuclear proliferation” in the Pacific. “Implication is that this is not something with (sic) #nuclearfree NZ should associate,” Clark tweeted in reply.

Clark further quoted Patman, who said, '“Staying outside #Aukus would avoid reputational damage to New Zealand’s non-nuclear security policy in the eyes of other states, and complement the strategic goal of diversifying Wellington’s trade ties in the Indo-Pacific region.”

She agreed with Patman’s warning that it was “important NZ is clear-eyed about possibility that Aukus could constrain its foreign policy autonomy” and said it the possibility alone presented a case for remaining outside of Aukus 2.

The former prime minister said: “IMHO NZ needs a full public debate on this & not an officialdom-driven realignment. … Furthermore, detachment is consistent with #NZ’s distinctive worldview …”

Nuclear Free Act 1987

The direction of a growing New Zealand militarism could indeed raise questions over the future of the country’s nuclear free policy.

In 1984, after decades of campaigning against nuclear testing in the Pacific and increasing public objections to visiting U.S. warships, New Zealand under the then Labour Prime Minister David Lange, banned nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships from using its ports and waters.

Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, the country became a nuclear-free zone.

That legislation is seen as a defining exercise of national sovereignty and became part of New Zealanders’ cultural identity, particularly after French secret service agents in 1985 bombed Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior vessel, moored at Auckland harbour, to prevent it leaving for further protests against France’s nuclear tests at Mururoa Atoll. One crew member was killed.

The Act prohibits “entry into the internal waters of New Zealand 12 nautical miles (22.2km) radius by any ship whose propulsion is wholly or partly dependent on nuclear power”. It also prohibits any New Zealand citizen or resident “to manufacture, acquire, possess, or have any control over any nuclear explosive device”.

When the AUKUS deal to help Australia build nuclear-powered submarines was announced in September 2021, then Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said the submarines would be banned from entering the nuclear-free zone, but the deal wouldn’t change New Zealand’s Five Eyes security and intelligence ties.

The Road to AUKUS

The U.S. has been involved in efforts to contain China in its own backyard, while dangerously increasing tensions between Beijing and Taiwan. This has involved increased diplomatic support for the Taiwanese independence movement as well as concluding weapons deals with the self-governing island, which China sees as an integral part of its own territory.

Official US policy also recognises Taiwan as part of the People’s Republic of China.

AUKUS could play a central role in a U.S. containment strategy. Australia confirmed in March it would buy three U.S.-manufactured nuclear submarines for A$368 billion ($391 billion) over the next three decades, with an option of buying two more, as part of the AUKUS pact Pillar 1. Pillar 2 involves the sharing of information in defence technologies.

The AUKUS deal has been controversial in Australia and increases tensions between Canberra and Beijing. Australia’s decision to join AUKUS and enter into the submarine deal was concluded by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese without consultation with Parliament, let alone with the Australian people.

AUKUS has been criticised by former Australian Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating. In a speech to the Australian National Press Club in March, he said:

“We are now part of a containment policy against China. The Chinese government doesn’t want to attack anybody. They don’t want to attack us … We supply their iron ore which keeps their industrial base going, and there’s nowhere else but us to get it. Why would they attack? They don’t want to attack the Americans … It’s about one matter only: the maintenance of U.S. strategic hegemony in East Asia. This is what this is all about.”

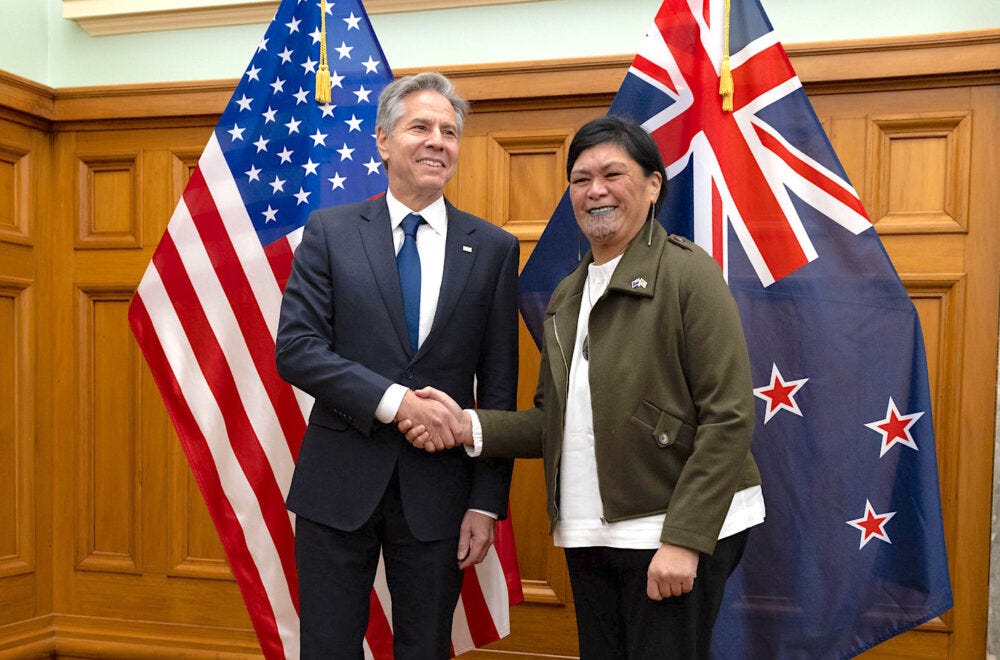

Blinken in New Zealand

After US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Wellington last month, New Zealand Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta told media the government was not contemplating joining AUKUS.

However, a new Defence Policy and Strategy document, one of a raft of recent government papers on the issue, said: “AUKUS Pillar 2 may present an opportunity for New Zealand to cooperate with close security partners on emerging technologies.”

During his own press conference with Blinken, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins said the government was “open to conversations” about AUKUS membership.

Three decades after it took the country out of ANZUS (consisting of Australia, New Zealand and the US), Labour would turn full circle if it signed up to the AUKUS pact while in power. The U.S. suspended its obligations to New Zealand under the 1951 ANZUS Treaty in retaliation for the nuclear-free policy introduced in 1987 by Labour.

A decision to join AUKUS will be one for the next government after October’s general election. According to recent polling, the country’s right-wing opposition party, National, could govern alongside the far-right, libertarian Act Party.

‘Don’t need enemies where enemies don’t exist’

Other dissenting voices beside Clark’s were largely absent in the New Zealand mainstream media. Yet there is deep unease in some quarters over how the security state documents collectively frame China as a threat to the strategic balance in the region, portraying it as the one country New Zealand must prepare to face militarily.

In Context spoke with National Party foreign affairs and defence spokesman Gerry Brownlee, who said that the ruling Labour Party’s position on AUKUS — and on defence in general — had shifted much closer to his own party in recent years.

He said New Zealand’s proposed involvement in AUKUS had yet to be defined and there would be no immediate moves to join the alliance.

He was cautious, however, about jeopardizing trade with China and emphasised a need to protect and promote what he called New Zealand’s liberal democratic values.

“We don’t need to make enemies where enemies don’t exist, but we need to keep our eyes open and look at all the risks,” he said.

Former general-secretary of the Labour Party, Mike Smith, said discussions within the Labour government over AUKUS were ongoing.

“My understanding is that officials have been tasked with investigating the pros and cons of what AUKUS Pillar 2 might involve and that a paper on this will be brought to Cabinet in due course,” Smith said. “I think the issue is not settled yet inside this government and there will certainly be debate outside the official process.”

Smith said he didn’t believe the country’s nuclear free position was under immediate threat but he remained wary.

“I think there are some among our officials who think that New Zealand’s nuclear free legislation has passed its use-by date. I do not see any possibility of it being changed in the near term, but I think this view should be flushed out,” he said.

He backed former Labour Prime Minister Clark’s comments that the recent spate of security and defence documents were Five-Eyes “copy and paste” jobs.

“I think there is a great danger that New Zealand’s foreign policy is being led by the security agencies prioritising US-led Five Eyes strategies focused on China, which poses no threat to New Zealand but does threaten US unipolar dominance and neoliberal economics,” Smith said.

“China offers development for mutual prosperity in a multipolar world and the U.S. demands we purchase arms from them for use in possible war, which means a large opportunity cost to the detriment of our social policy,” he added.

Approximately a quarter of all New Zealand’s export trade is destined for China.

‘We want nothing to do with AUKUS’

Indigenous party Te Pati Maori co-leader, Rawiri Waititi, agreed the security state documents were politically coloured in a way that did not present objective facts on the country’s security. “Government agencies and government bureaucrats are not apolitical,” said.

Waititi poured cold water on a New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS) report that China should be a concern for New Zealand.

“There is no specific evidence supporting the narrative that Russia, North Korea and Peoples Republic of China (PRC) are interfering in Aotearoa’s [New Zealand] politics,” he said.

“There is clear evidence that repurposed white supremacy from the USA is the major threat to our democracy given the digital hate traffic directed at Maori.”

The New Zealand spy agency also warned rising social and economic inequality — as inflation and a global downturn created further hardship — were expected to contribute to the radicalisation of violent extremists in New Zealand. It admitted the main threat of violent extremism came from white supremacists.

On the broader security and defence themes, Waititi was adamant.

“We want nothing to do with AUKUS. We want nothing to do with nuclear-powered or armed naval capacity,” he said.

“Our Nuclear Free Act 1987 is a guiding principle and military neutrality is a natural evolution of that policy. Internationally, Aotearoa must be friends to everybody and enemies to nobody,” Waititi said.

The Security State’s Arguments

NZSIS published its unclassified report on August 11, identifying what it calls rising strategic competition, technological innovation, global economic instability and falling public trust as factors driving violent extremism, foreign interference and espionage.

Following the U.S. line, the report claimed China, Russia and Iran were responsible for instances of foreign interference, mainly the monitoring of expatriate communities, posing a potential risk of significant harm.

The spy agency warned that foreign nations would more likely resort to espionage and interference to advance competing visions of regional and global orders as “opportunity for statecraft” diminished amid rising geopolitical tensions. It did not say who would be responsible for this loss of opportunity. The report said:

“What is foreseeable is that an increasing competition between states creates fewer opportunities for more collaborative approaches to statecraft. As a result, we see greater incentives for states to reach for covert tools such as espionage and interference. This situation is especially evident in an environment where some states are moving away from, and attempting to rewrite, accepted international rules and norms of state behaviour. In a complex strategic environment, more states are likely to turn to intelligence to avoid surprise and gain an advantage.”

The agency said China’s efforts to expand its power in the Pacific was a “major factor driving strategic competition in our home region.”

The NZSIS document added:

“PRC has significant and growing intelligence and security capabilities, and its efforts are increasing New Zealand’s exposure to the consequences of strategic competition.”

Defence Policy & Strategy Statement

A week earlier New Zealand Defence Minister Andrew Little had introduced three other security and defence documents to the public at Parliament in Wellington.

He told a select crowd that included diplomats, academics and MPs:

“We no longer live in a benign strategic environment. … We must be prepared to equip ourselves with trained personnel, assets and material, and appropriate international relationships in order to protect our own defence and national security – and we are.”

One of the documents, the 37-page Defence Policy and Strategy Statement, focused on the need to make the country’s military “operationally credible,” enabling it “to act earlier to prevent threats, for example through increased presence, as part of broader New Zealand efforts and in concert with international partners.”

“Where possible, Defence will seek to act to constrain hostile actions, will be prepared to employ military force, and engage in combat if required,” it added.

The statement stated the goal would be to prevent states that don’t share the country’s “values” from establishing a “military or paramilitary presence” in the region. It advocated greater New Zealand military deployments in the Pacific region.

Like the spy agency report, the document flagged China’s “political, economic, and security influence” in the Pacific, which it claimed was “at the expense of more traditional partners such as New Zealand and Australia.”

“An increasingly powerful China is using all its instruments of national power in ways that can pose challenges to existing international rules and norms,” it said.

“Beijing continues to invest heavily in growing and modernising its military and is increasingly able to project military and paramilitary force beyond its immediate region, including across the wider Indo-Pacific.”

The statement makes no mention of the steady build up of U.S. forces in the region, including new bases near China, such as in Australia and the Philippines, as well as naval assets patrolling the South China Sea. The statement does not entertain the possibility that China’s military activity is defensive in response to the growing U.S. presence.

A Future Force Design Principles document in addition sets out how the military would be reconfigured to meet these supposed new threats.

The release of these defence documents came after a Defence Policy Review, commissioned by the government in 2022.

National Security Strategy

A new, US-style National Security Strategy, the first of its kind in New Zealand, delineated 12 main areas of concern to security agencies, including strategic competition, disinformation, foreign interference, terrorism, economic security, Pacific security and cyber, border, maritime and space security.

It pointed to potential flashpoints in Taiwan, the South China Sea and East China Sea.

The strategy noted China’s efforts to build ports and airports in the Pacific, which it said could have both civilian and military purposes.

“The 2022 China-Solomon Islands security agreement and ongoing attempts to create new groupings in the Pacific demonstrate China’s ambition to link economic and security cooperation, create competing regional architectures, and expand its influence with Pacific Island countries across policing, defence, digital, and maritime spheres,” it said.

The document emphasised it was important for New Zealand to partner with other nations tied to the Five Eyes intelligence apparatus, as well as others, including Japan and South Korea.

It gave direction to New Zealand’s intelligence community to navigate the emerging geopolitical terrain, including the publication of an annual threat report, alongside a ministerial speech, as well as building trust among the public.

The plans will now cost billions of dollars. New Zealand spends approximately 1 percent of GDP on defence. Little said he expected that would rise, but that it was unlikely to reach to 2 percent, the level spent by Australia and some NATO-aligned countries.