Opening the door to the Devil

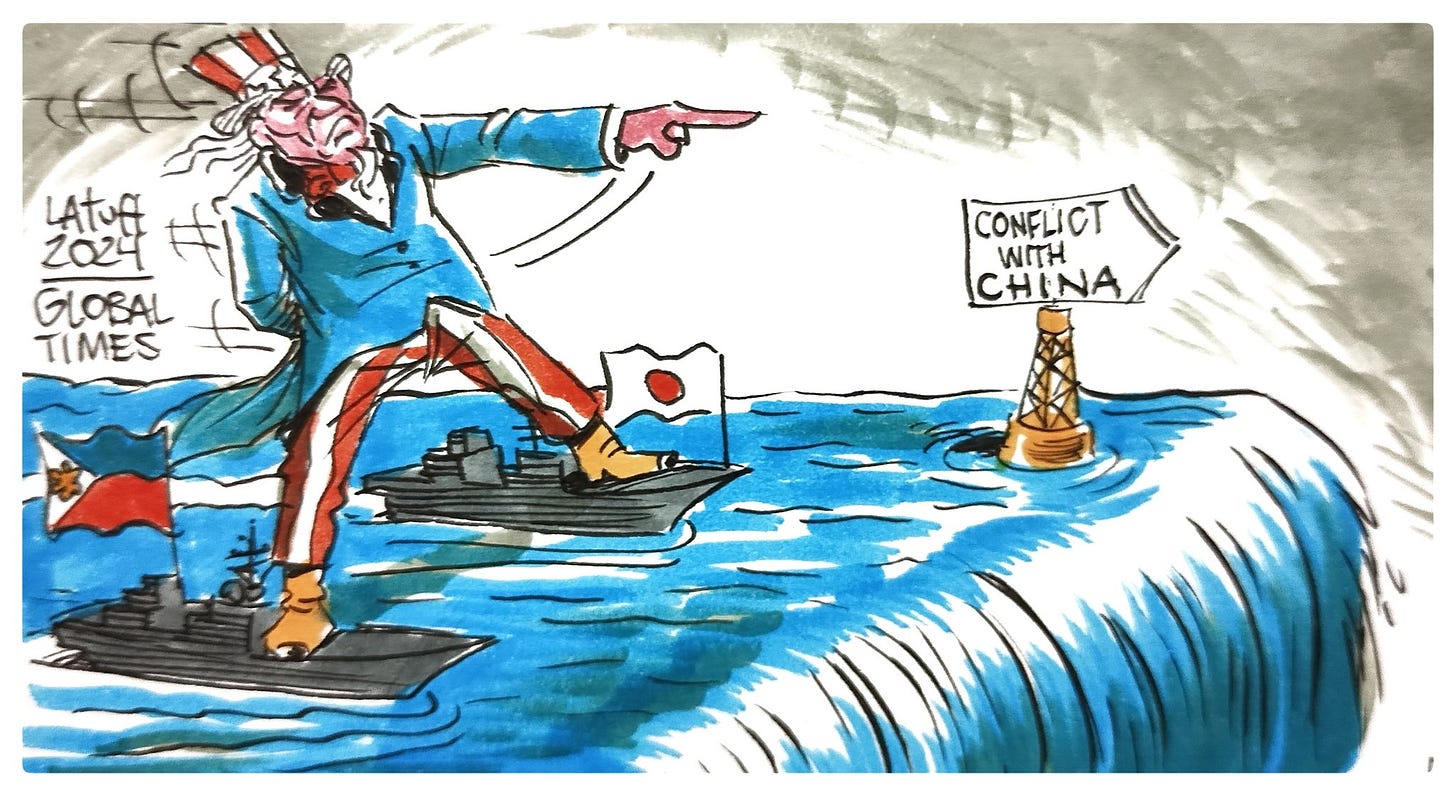

As Japan, New Zealand and the Philippines all move closer to US-led military architecture in the Asia-Pacific region, experts warn of the consequences.

This story was first published by Consortium News

Political tensions are increasing in the Asian-Pacific after engagements in Washington produced statements pointing to New Zealand, Japan and the Philippines moving towards greater integration into US-led military blocs.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and US President Joe Biden attended a trilateral summit on Thursday, 11 April, where they announced an agreement enhancing military operation, including joint naval exercises alongside Australia in the disputed South China Sea.

It followed a joint statement on Tuesday, April 9, by Australia, the UK and the US confirmed Japan was a candidate to join ‘Pillar II’ of the nations’ AUKUS nuclear submarine alliance, established as part of preparations for war with China.

New Zealand, Canada and South Korea are also being touted as Pillar II candidates.

Pillar II is slated to involve technology sharing in areas like artificial intelligence, underwater drones, quantum computing and hypersonic missiles.

China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said signalling of the bloc’s expansion would further escalate an arms race “to the detriment of peace and stability in the region”.

The trilateral meeting coincided with a visit by New Zealand’s Foreign Minister Winston Peters arrival in Washington, where he released a joint statement with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken that claimed there was a compelling need for New Zealand to work more closely with the US-led “frameworks and architectures” in Asia-Pacific.

The April 11 statement said: “We share the view that arrangements such as the Quad, AUKUS, and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity contribute to peace, security, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific and see powerful reasons for New Zealand engaging practically with them, as and when all parties deem it appropriate.”

Former New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark, the most high-profile critic of the country’s continued drift away from an independent foreign policy, interpreted the statement as a precursor to joining Pillar II. She said the decision would be undemocratic, as the government had not campaigned on the issue and so had no popular mandate to sign up to the pact.

She told the Q+A TV programme: “The issue is do we keep our heads and say ‘does what we’re doing contribute to trying to lower tensions, or does it contribute to raising them’. It’s an open secret that AUKUS… is aimed at China. China also happens to be the biggest trading partner for New Zealand twice the size of Australia’s export take from us and rather more than the US. So, something quite doesn’t add up here.”

The escalating security dilemma amid moves by the US to encircle China with more military bases, while enlarging AUKUS, is worrying many in the region.

“I was at an ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] workshop in Jakarta in January and it's pretty clear that everybody in the Pacific is worried,” associate professor for neutrality studies at Kyoto University, Pascal Lottaz, said in an interview.

“ASEAN is worried about what to do if a war breaks out because the rhetoric coming from the US and from China is just so extremely bellicose. When people say like, ‘there was going to be war within the next five years’ or by 2025 that worries everybody. And it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

What adds up for Lottaz, like many geopolitical analysts, is that military bloc expansion within a region of trade interdependence and relative peace forms part of a calculated effort to maintain US primacy now dangerously playing out.

“I do view this as an outgrowth of the emerging multipolarity and the US trying to subdue China,” Lottaz says.

With the ‘unipolar moment’ of US hegemony now ending, as centres of power extend south and once again to the east, Washington is nevertheless pursuing its doctrine of full spectrum dominance in efforts to contain its peer competitors.

The futility as well as danger of this approach may be underlined by the fact that even states like Iran and South Africa can effectively determine the direction of geopolitical events in defiance of US pressure.

“We’ve never had a moment when smaller partners, smaller parts of the system, could really defy the larger ones,” Lottaz says.

“We've never had a situation where South Africa could through the courts really impact world events or how world events are perceived. I'm also talking militarily. Look at how North Korea has very successfully defied not only the US but also China to build nuclear weapons and look where that got North Korea compared to Iraq.

“We also see how the West is not able to subdue Russia and is now getting this huge pushback from the Global South. So, this multipolarity will not inherently change what countries want, but it will change what countries can do and then the question is, will this lead to a management of the situation or is it going to lead to more war.”

The trilateral agreement between the US, Japan and the Philippines is likely to alarm China due to its possible outworkings in the South China Sea and concerns over increased US access to neighbouring coastal bases, particularly near conflict hotspot Taiwan.

It may also signal to its neighbours that they can play hardball in the South China Sea if they so wish, as the US offers protection. The US has been engaged in ‘lawfare’ against China, using regional disputes in an attempt, some argue, to secure a grip on shipping lanes China’s economy depends on.

In July, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that China’s claims to “rights and resources” with the nine-dash line, which encompasses about 90 percent of the South China Sea, had no legal basis.

China rejected the arbitration, while insisting it was committed to resolving disputes with its neighbours.

The Philippines became independent from the US in 1946 and Treaty of Manilla defined Filipino territory as based on the earlier Treaty of Paris, when Spain ceded the Philippines in 1898.

It excluded all territories that are in dispute today, including all of the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal.

The Philippines began contesting those territories in 1972 when the government invented Kalayaan, a new municipality that comprised a large portion of the Spratly Islands.

The expansionist move irked those nations also claiming rights to the contested spots, which include China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Brunei and Malaysia.

Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte decided against rallying behind the decision and instead focused on diplomacy, hoping his non-confrontational approach would make an impression.

International relations expert, Otago University’s Professor Robert Patman, said the trilateral agreement could contribute to tensions, but that China could have avoided it altogether.

“China itself is its own worst enemy because it didn't accept the Hague tribunal's ruling when the Philippines took China to the international court,” he said it an interview.

“So, it's not surprising that there's been continued tensions between the Philippines and China over different territorial claims. There are about seven claimants in the South China Sea. China, if it had accepted that finding, could have diffused things considerably and they haven't. They ignored it and unfortunately, this is a pattern with Great powers upholding the rules, or rules-based order, until it contradicts their interests.”

Lottaz agrees. He says:

“Duterte’s strategy failed and so now Marcos Jr is going in the other direction and saying ‘well, if being nice doesn't work, then let's just allow the Americans to have more bases over here’. That's what he's doing and the Americans are now very happy expanding their bases network.”

Marcos Jr told media at the weekend the new trilateral agreement would “change the dynamic” in the region.

The Philippines may now increase the number of military bases the US can access and is expanding port facilities in the Batanes Islands, just 125 miles south of Taiwan. The US military last week also announced the deployment of a Typhoon Mid-Range Capability (MRC) missile system to island of Luzon 250km from Taiwan.

Lottaz calls the trilateral summit in Washington a show of political unity, but also a further sign the US is pushing a militarization of Japan and the Philippines’ relationship and that a formal alliance is being charted.

Japan has formidable military and technological capacity, but its passivist constitution imposed by the US after World War II restricts it from having a conventional standing army.

The Japanese Self Defence Forces (JSDF) have been geared towards internal security, although that is changing. Japan is an Indo-Pacific NATO partner, alongside South Korea and New Zealand. It has contributed to NATO operations in Afghanistan and the Balkans and maintains interoperability with the alliance. A NATO liaison office is being set up in Tokyo this year to co-ordinate with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

Kishida also announced last year Japan would double military expenditure to two percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and change military policy allowing it to strike targets abroad.

However, moves like joining Pillar II and sending troops abroad would involve a huge shift it both policy and attitudes in Japan.

Nothing short of a direct attack on the country could possibly remove the constitutional articles governing its military remit, Lottaz says.

“Two thirds majority of Parliament would need to say yes to changing the constitution and then 50 percent of the population in a referendum - double mechanisms, a double lock, which is why it's so hard to change.”

New Zealand’s move towards Pillar II and NATO has also been incremental. But under its right-wing coalition voted in last year, the journey towards integration has accelerated, as its foreign minister’s joint statement with Blinken demonstrates.

Before Winston Peters’ US trip he had attended a NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs meeting in Brussels on April 3-4, after meeting Polish and Ukraine government officials over the US proxy war with Russia.

Peters said he expected to conclude talks on an Individually Tailored Partnership Programme (ITPP) with the US-led alliance “in the coming months," an agreement expected to involve significantly greater financial and military assistance to Ukraine as part of collective efforts to maintain the so-called “rules-based international order”.

New Zealand Defence Force soldiers are currently training Ukraine’s military in the UK.

Like Japan, New Zealand is constrained by its own constitution, which includes a nuclear free law banning nuclear-powered and armed ships from its territory.

Former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison at the weekend urged New Zealand to abandon the legislation introduced in 1987, an unlikely scenario given a current bipartisan position on its anti-nuclear tradition. At present AUKUS submarines would be excluded from New Zealand waters.

Pillar II is being pushed as a ‘non-nuclear’ aspect of AUKUS, but as China’s ambassador to New Zealand Wang Xiaolong, writing for Newsroom, pointed out on April 11, “Voices claiming that Pillar II is not violating the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) requirements neglect the interlinks between the two Pillars. The sole purpose for Pillar II is to support and serve Pillar I, either financially or technologically.”

He adds: “And if you read carefully the latest announcement by the AUKUS members, you’ll easily find that one critical reason to invite more participants is to consolidate the dominance of a certain country in the ‘Indo-Pacific’ and shift and spread the exorbitant cost.”

Patman points to considerable pushback in Australia over AUKUS’ cost. Canberra is hoping for delivery of Virginia-class nuclear submarines from the US in the interim, sometime in mid-2030, while new SSN-AUKUS submarines are being built at an approximate cost of A$368 billion (US$239b).

He believes not all nations weighing up Pillar II involvement will be joining any time soon in any case, and in particular Japan, due to tight security rules about sharing technology with partners.

Like others, Patman fails to see New Zealand’s national interests being served by AUKUS membership, a military bloc eyeing war against a country where 30 percent of its exports are destined annually. The same could be said for all Asia-Pacific nations. There could be immediate repercussions for joining for New Zealand, as well as catastrophic consequences in any future war against what looks like an imagined enemy.

“The Chinese ambassador to New Zealand was very clear on this in February when he said that New Zealand is a sovereign state and it's free, if it chooses, to join Pillar II of AUKUS,” Patman says.

“But he made it clear that China opposes AUKUS which it sees as a Cold War construction and he said - and this was a very subtle point – that in areas there would be consequences for New Zealand, including for its economy. This was a veiled warning, in my view, to the farming community, which is the backbone of the country in terms of economics… The Chinese ambassador was reminding a National Party-led government that their core constituency could be disadvantaged.”

More fundamentally, as Pacific historian and foreign policy activist Marco de Jung remarked after the Washington joint statement, “AUKUS causes the very instability it claims to address. New Zealand is better using its limited resources to support Pacific-led regionalism against superpower competition.”

Out of the blue (or not) Luxon signs a defense agreement with Philippines: https://youtu.be/NiiGDu2euJY?si=XO9NZucSjzaBnSfh . Anyone see a script unfolding ?AUKUS2 or not …momentum strong . What mandate from the NZ public?

Geopolitical commentary Australian style : Bob Carr on AUKUS II https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkxfpths1h8J3kMaUvpFlcUu_8UCXXRPYQQ?si=U_BtdoKd0sdir7fs