Kitson's legacy - a blueprint for countering subversion in the West

Britain’s General Sir Frank Kitson, who died recently, established a sinister political-military doctrine for fighting the IRA, but warned it may need to be used domestically in Britain.

This story was first published by Consortium News as a two-part series.

For Irish human rights lawyer Kevin Winters, Britain’s counter-insurgency campaign throughout Northern Ireland’s “Troubles” can be traced back to one man — General Sir Frank Kitson.

The conflict took 3500 lives, a relatively low number compared with other conflicts, but one that belies a ferocious clash of wills between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the British state, including its paramilitary loyalist proxies.

It can be argued Kitson, who died at the start of January, was chief architect of the torture centres, death squads, psychological operations, extra-judicial killings and an illicit network of agents that featured across 30 years of Anglo-Irish conflict.

For many, Kitson left behind a terrible legacy in Ireland, as well as a lasting sense of apprehension in Britain where he had cautioned similar methods may need to be deployed against “political extremists”. Many on the British left saw his book Low-Intensity Operations: Subversion, Insurgency & Peacekeeping (1971) as a blueprint to suppress dissent.

Northern Ireland was one of several parts of the world where he left his mark while in the British Army. Having lectured at the Rand Corporation during the 1970s, his tactics were undoubtedly exported even further, via the CIA. Evidence of his tactics can be found in places like Iraq.

What makes his time in Ireland stand out is that the crimes he helped to perpetrate were not in a distant colony. They occurred in Western Europe, right up until the 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement, seemingly under the direction of successive British governments and obscured by its agencies.

A year after Northern Ireland descended into chaos in 1969, Kitson arrived at Palace Barracks near Belfast as a brigadier. He got to work setting up and overseeing an army intelligence network and “counter-gangs” made up of covert army operatives.

They were sent out to kill IRA activists on sight, or engage in actions to force a change in the behaviour of the organisation or its support base, including using terror to induce war wariness.

Later, such counter-gangs would be largely made up of loyalist paramilitaries aligned with Britain, controlled surreptitiously by the military and police Special Branch.

“I think it all harks back to Kitson,” Winters tells In Context.

“He was definitely at the apex of that policy. You’ve got him there two years at the start of the conflict and he put the template in place within a very short period of time, which then had really long innings after his departure.

“The out-workings of his ‘counter-gangs’ and other techniques morphed and evolved over the years during the conflict to become, I suppose, more sophisticated, but essentially, I think the starting point is that he adopted everything that had been in play in colonial Britain where insurgency took place and deployed it in Britain’s ugly backyard…

In the 1980s and early 1990s, loyalist paramilitaries got ever more sophisticated in terms of targeting republicans, ranging from political leaders, Sinn Fein to IRA activists, to solicitors seen as republican sympathisers. They were getting ever more high-grade intelligence and I lay the blame of that to the door of Kitson.”

Kitson sought to adapt and use what he recognised as “out of date” colonial methods of counter-insurgency he had helped brutally employ in places such as Kenya to suppress the Mau Mau uprising, as well as in Oman, Malaya (Malaysia) and Cyprus.

In 1950s Kenya, Kitson set up gangs of British-friendly Kikuyu tribesmen, who helped ambush Mau Mau fighters in their forest hideouts, or tracked their bases down for British bombers to target them.

He believed that applying more oblique versions of such tactics in a Northern Irish context would involve “an extended period of trial and error”.

Hiding Behind the Law

Low-Intensity Operations argued the law needed to be bent to meet the needs of the army, with its counter-insurgency either fitting into or hiding behind the legal framework of Britain’s modern liberal democracy.

In theorizing about the security state, his writing presents contradictory positions that go to the heart of his doctrine of military necessity, namely the notion that in countering insurgency and subversion the military must transcend the rule of law by stealth so it can best protect it.

He wrote that equality before the law as a functioning principle was morally desirable, so that “officers of the law will recognise no difference between the forces of government, the enemy, or the uncommitted part of the population.”

However, he argued that sometimes, of necessity, the “law should be used as just another weapon in the government’s arsenal and in this case, it becomes little more than a propaganda cover for the disposal of unwanted members of the public.”

Discovery of these “Kitsonian experiments,” bringing them into the light of day in court and securing compensation to the state’s victims, has been something to which Winters and his associate litigator Christopher Stanley, alongside victims’ groups and other lawyers, have dedicated many years.

Kitson left Northern Ireland in 1972 after a series of atrocities committed by the British Army and with an IRA target on his back. He took up various roles, including adviser to the Ministry of Defence. He retired after becoming commander-in-chief of the UK Land Forces from 1982 to 1985 and acting as aide-de-camp general to Queen Elizabeth II from 1983 to 1985.

Although Kitson’s writings and lectures left a lasting impression on Western security experts and military strategists, his name was largely forgotten after an uneasy peace took root across the north of Ireland.

Case against Kitson and MoD

That changed in 2015 when Winters’ legal team served legal papers on Kitson and the British Ministry of Defence (MoD), accusing them of complicity in a 1973 grenade attack on a bus by loyalist paramilitaries in east Belfast that killed Catholic man Eugene Patrick Heenan.

The civil action created headlines and brought renewed attention to the way the government and Kitson’s military boss Harry Tuzo, general officer commanding and director of operations in Northern Ireland, had given Kitson carte blanche to develop and pursue his dark, military-political ideology in Northern Ireland.

In what was meant to be a test case, the action argued that Military Reaction Force (MRF) member Albert “Ginger” Baker, who was convicted for the murder of Heenan and others, could be causally linked to Kitson.

Kitson, who had set up and run the 40-person covert MRF, was accused of “negligence, misfeasance in office and breach of Article 2” of the European Convention on Human Rights, the right to life.

Winters at the time said:

“These are civil proceedings for damages, but their core value is to obtain truth and accountability for our clients as to the role of the British army and Frank Kitson in the counterinsurgency operation in the north of Ireland during the early part of the conflict, and the use of loyalist paramilitary gangs to contain the republican-nationalist threat through terror, manipulation of the rule of law, infiltration and subversion - all core to the Kitson military doctrine endorsed by the British army and the British government.”

Winters and Stanley decided not to pursue the conventional approach of suing the state in a corporate capacity or pushing for an inquiry. They viewed civil proceedings as a potentially better way to achieve disclosure and force details of the “dirty war” into the open.

Winters believes the controversial Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill was passed through the UK Parliament last year in part to stifle the “latent threat” posed by civil litigation, which compels former security force members and politicians into court.

The bill offers immunity to those accused of murder on condition they cooperate with a commission set to investigate over 1000 “unsolved” killings. He says:

“With civil litigation, acting on behalf of plaintiffs, on behalf of families and victims, you have an awful lot more control and clout and input into the litigation and legal process compared to Police Ombudsman, Police Investigation and Inquests, where you’re pretty much at the behest of the state in terms of funding, resources, timing, release of information, releasing disclosure, etc. You are kind of reactive to those processes. In civil litigation, you are proactive and you can take hugely lateral approaches.”

Official inquiries hindered

Official inquiries into state-run death squads and extrajudicial killings have also seen those leading the investigations hindered by the same state and security apparatus being probed.

The first of several was led by English cop John Stalker in 1984, who attempted to probe the killings of six unarmed IRA men over a five-week period of 1982, all shot dead by police. His “shoot-to-kill” inquiry faced obstruction and Stalker was threatened, smeared and finally removed from the inquiry.

More recent inquiries have faced less overt hostility, but their reports have been limited by scope and politics, including Sir John Stevens’ three inquiries into state collision with loyalist paramilitaries.

Stevens concluded in 1990 such activity was “neither widespread or institutionalised.” However, by 2003, Stevens said he had found collusion at a level “way beyond” his 1990 view.

Stevens also faced high-level obstruction, including a tip-off in January 1990 that allowed British army agent Brian Nelson to flee before he was arrested for questioning by the Stevens team. Nelson had directed loyalist paramilitaries to target the state’s enemy’s by providing classified army intelligence reports and had helped arrange an arms shipment from apartheid South Africa to loyalist factions in the late 1980s.

Stevens’ inquiry headquarters were burnt down the night before the planned arrest, after phones were cut and fire alarms disabled. He said he believed the incident was a deliberate act of arson that had not been properly investigated.

Peter Cory, a retired Supreme Court of Canada judge, probed six killings where security force collision with paramilitaries was alleged, including in the murders of human rights lawyers Pat Finucane (1989) and Rosemary Nelson (1999).

The Heenan case has been parked in the High Court for nearly four years on a strike-out motion by the British Ministry of Defence. Kitson was never compelled to attend court.

As new evidence became available, Winters and Stanley decided to go with a separate murder involving Baker that they believe presented more compelling evidence to get a state collision test case over the line.

Winters says:

“There are all sorts of other reasons why we decided not to run with Heenan and decided to run with another case. There are a series of other cases linked to Albert Ginger Baker. There’s a cohort of litigation, six or seven cases that we have all directly or indirectly linked to Baker. And, again, we see this as a series of cases that were strong enough to warrant issuing a writ against Frank Kitson himself.”

Kitson’s ‘firm grip’

In a long obituary by the UK establishment broadsheet The Daily Telegraph on January 4, General Sir Frank Kitson’s time in Northern Ireland is summarised in one paragraph:

“Promoted to brigadier, he took command of 39th Air Portable Infantry Brigade in Belfast in 1970. He took a firm grip on the divided city, taking down the barricades and sending his men into the former ‘no-go’ areas. He was appointed CBE for gallantry. In retirement, he gave evidence to the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday.”

The summary whitewashes the nature of this “firm grip.” In 1971, the Parachute Regiment entered the Ballymurphy housing estate in west Belfast, an IRA urban stronghold, looking for activists to round up as part of Operation Demetrius (internment without trial). They shot dead 10 civilians.

A year later the same regiment, known within military circles at the time as “Kitson’s private army” killed 14 unarmed civilians taking part in a civil rights march in “free” Derry, another “no-go” area for civil authorities. The incident became known as Bloody Sunday.

Terror became a tactic not only in the streets, but also in military holding centres. In August 1971, 14 men were taken from Long Kesh internment camp to a secret torture centre near Ballykelly in Derry and subjected to the “five techniques” for nine days straight.

They were hooded, made to stand in a prolonged stress position against the wall, subjected to a “white noise,” while deprived of sleep, food and drink. They were also thrown out of helicopters after being told they were above the Irish Sea, only to fall several feet to the ground. The men were never the same afterwards, suffering mental and physical health afflictions.

In a case brought by the Republic of Ireland, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in 1978 found use of the techniques “inhumane and degrading treatment.”

In June last year, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) apologised to the “Hooded Men” for not pursuing charges against the military at the time. It followed a UK Supreme Court ruling in 2021 that the techniques should have been characterised as torture.

There is evidence the techniques were used elsewhere. In 2003, Iraqi Baha Mousa died after interrogation by British soldiers. At an inquiry into his death in 2009 it was revealed he was subject to the same treatment as the Hooded Men.

In June 2023, Francesca Albanese, the UN’s special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, delivered a report to the Human Rights Council. It contained a description of Israeli treatment of Palestinian detainees that could be considered remarkably similar to the five techniques, “being hooded and blindfolded, forced to stand for long hours, tied to a chair in painful positions, deprived of sleep and food, or exposed to loud music for long hours; and being punished with solitary confinement”.

Communal terror

Christopher Stanley, Kevin Winters’ associate, believes the techniques were a way to create terror among the Irish Catholic population in Northern Ireland.

“The deliberate use of the five techniques wasn’t for intelligence gathering, it was to send a message back to communities,” he says.

The same was true for the Ballymurphy housing estate in west Belfast, he adds.

“There were no IRA men in the Ballymurphy estate, they’d all pissed off down south of the border. So, there is that sort of collective retribution.”

Ciarán MacAirt, manager of the state victims’ charity Paper Trail, says the Ballymurphy massacre was an act of repression and suggestions the action was the result of undisciplined soldiers a damage-limitation claim.

He says archival evidence shows paratroopers involved were reporting upwards and that these reports differed from what the army told the media at the time. The army said they had come under fire and those killed were IRA activists. At a subsequent coroner’s inquest decades later, army lawyers said the soldiers perceived a threat and soldiers acted without discipline.

There is evidence of collective punishment carried out by other army regiments in Belfast during the early 1970s, a pattern of civilian killings in response to soldiers’ deaths at the hands of the IRA, he says.

“In 1972, seven soldiers of the King’s Regiment were killed and scores injured in the Springhill/Whiterock area of west Belfast. That is obviously devastating for their loved ones. It is also true that this regiment left a trail of devastation in its wake as they killed civilians after their soldiers were killed and injured. The victims of the King’s Regiment included young school girls, teenagers and the local priest.”

Kitson’s Irish enemy

Kitson faced an implacable enemy in the IRA, a modern structural response to colonial occupation in Ireland that can be traced back several centuries.

The organisation had faded into obscurity after the failure of its 1950s border campaign, but came back with a vengeance after a civil-rights movement in the late 1960s, inspired by African-Americans, was violently suppressed by Northern Ireland’s regime based at Stormont.

Irish Catholics trapped in the northern statelet under Britain’s jurisdiction following the island’s war of independence and its subsequent partition in 1921, had faced systemic economic and social inequality, periodic pogroms and a gerrymandered electoral system that kept them in a state of perpetual powerlessness.

Northern Ireland had been created with an inbuilt majority of “unionists”, descendants of the original colonial Protestant “planters” of the 1600s, guaranteeing a sectarian status quo as part of Britain.

It was, in the words of its first prime minister, Edward Carson, “a Protestant state for a Protestant people”.

Threatened by a more assertive Irish Catholic population, sectarian mobs accompanied by the state’s paramilitary police and local militia displaced thousands during Belfast pogroms in 1969. Finding itself unable to defend the Irish Catholic population under siege, the IRA split, with the more militant “Provisional” IRA faction coming to the fore as the defenders of beleaguered communities.

It wasn’t long before defence turned to offense. The suppression of the non-violent civil rights movement and the British Army’s arrival in 1969 to reimpose “law and order” created rage and the objective conditions for a renewed armed struggle to end British rule in Ireland.

Bloody Sunday in particular acted as an effective recruiting sergeant for the Provisionals, with young Irish Catholic men and women joining in their droves.

‘I remember the yellow flame as he began firing’

Seamus McKearney was among them and he immediately came up against Kitson’s counter-gangs.

In 1972, McKearney was just 16 when he ventured out on his first IRA operation on the Glen Road in west Belfast.

A bright orange car slowed to a crawl in front of him and another activist. The back window was down and by the time McKearney saw the barrel of a weapon pointing out, the car was just metres away before they started to run.

“As the car slowed, I could see a man at the back with black greasy hair and a moustache aiming the submachine gun. I remember the yellow flame as he began firing, about 20 rounds at me and the person I was with,” he says.

It was McKearney’s baptism of fire. He was hit but escaped serious injury, unlike his associate, who was smuggled south across the Irish border to receive life-saving medical treatment.

McKearney went on to become an IRA commander in Belfast, an experienced gunman who would also take part in the IRA Maze Prison protest against Britain’s policy of removing the political status of inmates, a strategy aimed at criminalizing his movement. The “blanket” protest culminated in the deaths of 10 Irish hunger strikers in 1981 under the leadership of Bobby Sands.

At the time of his shooting, McKearney believed it was a random sectarian attack by loyalist paramilitaries. It wasn’t until a military lecture given by revered IRA leader Brendan “The Dark” Hughes at the Maze Prison in 1985 that he realised it was the work of one of Kitson’s covert military units and began to fully understand the rationale behind many of their attacks.

“The Dark presented a talk on Kitson and counter-insurgency and the methods the British used,” McKearney says.

“He described how the MRF had operated, carrying around seized IRA weaponry like Thompson submachine guns, firing from cars… He asked if anyone had experienced that and I thought ‘that happened to me.’ ”

McKearney says he identified the gunman as Sergeant Clive Williams, after seeing a photo of him in the media years later when the soldier received a medal for bravery in service to the Crown.

Unbeknown to McKearney at the time, in 1973 Williams stood trial and was acquitted at Belfast Crown Court for attempted murder of four civilians shot just weeks after McKearney was ambushed.

A BBC TV Panorama investigation in December 2013 found the Military Reaction Force carried out many such “drive-by” shootings of ordinary Irish Catholics. Kitson’s gangs weren’t just targeting IRA activists.

McKearney says Hughes’ lecture also focused on how Kitson’s targeting of Catholic civilians had attempted to trigger tit-for-tat reprisals from the IRA, to distract the group from engaging with the security forces and instead draw them into a vicious sectarian conflict.

“They were trying to spark retaliation and drag us into a sectarian war,” McKearney says. “The only people who would have benefited were the British… who could also better portray the conflict as one where they’re stuck in the middle of two warring tribes.”

McKearney lists three bomb attacks on bars in west Belfast that killed several people during 1976 as examples of such provocations. The IRA executed a number of local men after the organisation said they admitted to being agent provocateurs involved in the bombings while working for British military intelligence.

Stoking Sectarian Violence

By the mid-1970s, sectarian violence became even more vicious, with the rise of hyper-sadistic killings by a loyalist death squad known as the Shankill Butchers in Belfast, as well as by others, with Irish Catholics being assassinated after torture in “romper rooms”.

Fear stalked the streets of Belfast and the sectarian cauldron was being stoked by British military intelligence. A policy of reducing Britain’s regular armed forces and pushing the province’s Protestant police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and the local militia, the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) to the frontlines, further sectarianised the conflict.

The IRA had its share of successes against British military intelligence during the early period of the conflict, but much less so as the conflict continued.

Brendan Hughes, now deceased, played a key role in striking back at Kitson, even managing to tap phones at the army’s headquarters at Lisburn. After interrogating two captured Military Reaction Force operatives, Seamus Wright and Kevin McKee, he gained information that would later result in attacks on MRF fake businesses, killing several undercover soldiers. A massage parlour in north Belfast, an office in the city centre and a laundry van were hit simultaneously on October 2, 1972.

The MRF’s Four Square laundry operation used a van to collect intelligence when touting for custom around Belfast. Clothes were collected from homes and forensic tests run for traces of explosives, blood and firearms before the items were washed, dried and returned to residents.

“The Dark told us the captured agent provocateurs said they’d been trained at Palace Barracks in Holywood [M15 headquarters in Northern Ireland]. They gave the Four Square operation away, before being executed,” McKearney said.

The IRA ambushed the van as it entered the Twinbrook housing estate in west Belfast, machine-gunning it, killing Telford Stuart, although the IRA said two other soldiers were killed.

The MRF was disbanded in 1973 and replaced by the 14 Field Security and Intelligence Company, followed by the establishment of the notorious Force Research Unit (FRU) in the 1980s, which handled agents like IRA internal security boss Freddie Scappaticci.

Winters sued the Ministry of Defence on behalf of the family of the soldier killed in the Four Square botched operation. Minutes before talking with In Context he received word the MoD’s lawyers had signalled they wanted to settle the Telford Stuart case before it reached court.

“The family sued the MoD on the basis that the activities and failings exposed their relatives to risk of assassination and attack,” Winters says.

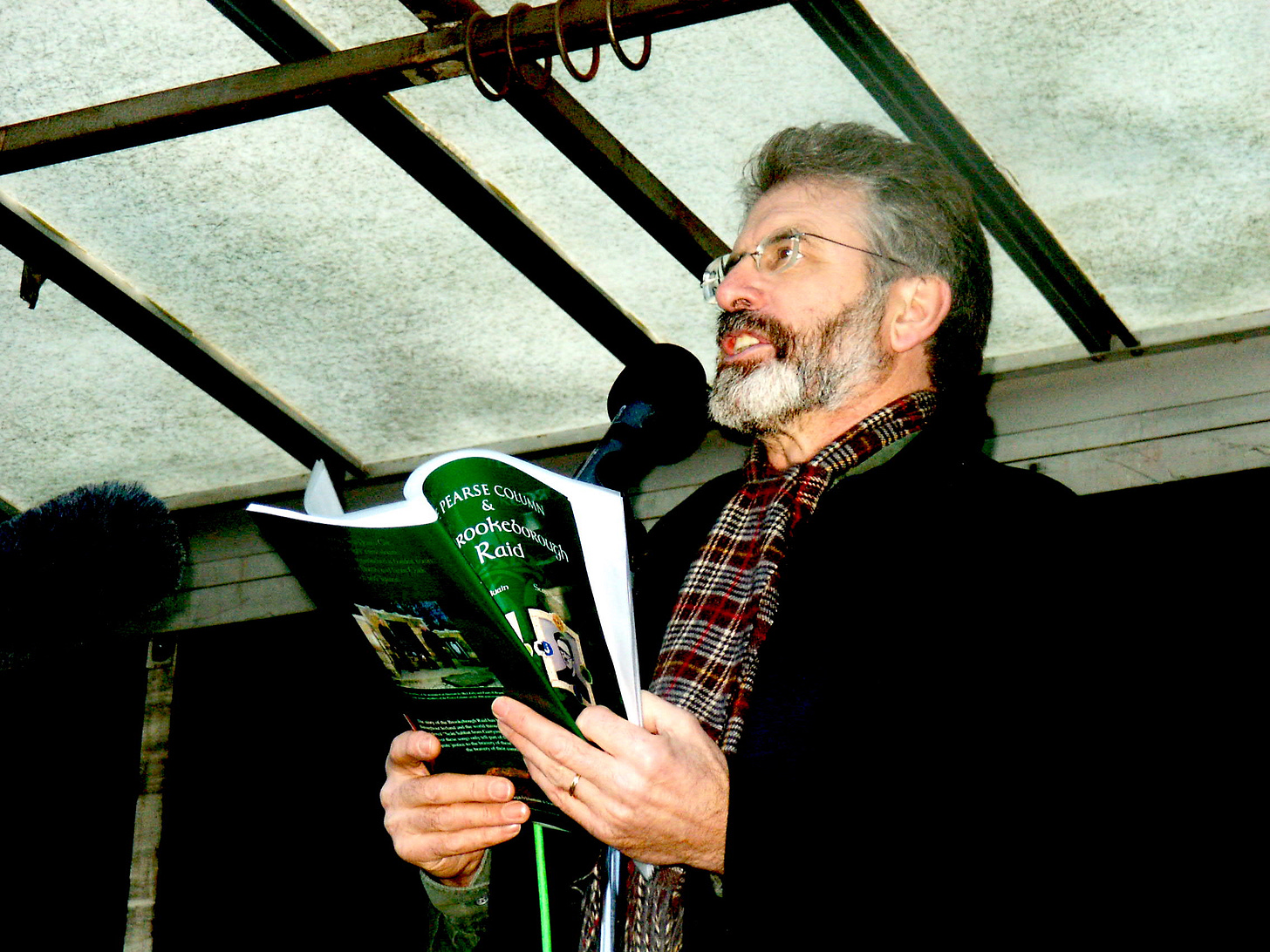

“I had a hunch that if we set this case down for trial, the MoD might want to talk… that we’d make bring them to the table, because the threat of witness subpoena, subpoenaing all and sundry, whoever is still alive, including [former Sinn Fein President and IRA leader] Gerry Adams, to see what people knew about this operation, was just far too toxic and the MoD and the Crown solicitors have seen fit to just try and negotiate this and settle it…

“I think this is an example of the latent threat and power of civil litigation. Four Square laundry was never going to be the subject of a criminal investigation, nor an inquest, because it was far too long ago… It’s out of time, the temporal jurisdiction is set down, the Supreme Court precludes Four Square laundry or other MRF cases from ever seeing the light of day.

“But civil litigation is so much more flexible and here we have this Kitsonian experiment of the MRF generally, and Foursquare laundry in particular, where Kitson’s hand is somewhere on that, and the state take a view and they’ve gone ‘you know what, rather than have a shit fest of civil litigation, where we don’t know what’s going to happen, we’ll take a pragmatic view, and we kill it off, pay out some damages and put it to bed.’ ”

There are now multiple cases where the MoD is seeking to settle. But the approach in some ways is a victim of its own success, as it means exposure of the inner workings of the state in perpetuating the crimes is limited.

“The spectre of ex-British army soldiers still alive, fit to come to court, looms large I think in the decisions of the MoD to shut all this down,” Winters says.

“The Kitsonian mantra put in place throughout all the sectors of the conflict is now going to find itself the subject of a vast number of settlements and resolutions, but without ever having a judicial input and analysis into these Kitsonian experiments.

So, there’s an element of disappointment, personally, that a court is never really going to get to grips with that. But on the other hand, anything involving Kitson — and if you look on the basis that his hand is everywhere — you’re going to have all these cases settling and a series of state settlements, these statistics say an awful lot as well.

To the man or woman in the street, whenever you settle in relation to a conflict-related case all those years ago, and the state pays out, even though there may not be fulsome apology, and even though there may be no admission of liability, collectively, case after case after case resolving and families getting damages at the door of a court, I think there’s some traction in that as well. I think that there’s some positive messages that can be delivered out of that.”

Threat of Kitson’s Experiments in West

A disturbing question remains after Kitson’s death concerning his legacy. Could Kitsonian experiments in Northern Ireland be a harbinger of what may come elsewhere, a wider barbarism prosecuted by state forces within other Western liberal democracies against their own citizens?

In Low Intensity Operations, Kitson wrote about the United Kingdom: “If a genuine and serious grievance arose, such as might result from a significant drop in the standard of living, all those who now dissipate their protest over a wide variety of causes might concentrate their efforts and produce a situation which was beyond the power of the police to handle. Should this happen the army would be required to restore the position rapidly. Fumbling at this junction might have grave consequences even to the extent of undermining confidence in the whole system of government.”

Kitson was capable of pursuing any method of defeating what he saw as subversion.

Ciaran MacAirt’s grandparents lost their lives in one of the more heinous crimes of the conflict — the bomb attack on McGurk’s Bar in north Belfast in 1971, which was linked to military intelligence. It killed 15 people and was blamed on the IRA by police. There is archival evidence Kitson acknowledged the cover-up.

“Kitson foresaw the time that his techniques may have to be used in Britain itself,” MacAirt points out. In a conversation with MacAirt in 2008, Colin Wallace, a former army intelligence figure in Northern Ireland and a psychological warfare specialist, put Kitson’s belief into a social and historical context. MacAirt says:

“Wallace described the period thus to me: ‘This was a time of the Red Threat. Unions were getting stronger… strikes and the three-day working week. We expected tanks to roll down Mayfair at any time. Northern Ireland, for us, was a social experiment.’ ”

Decades later in 2015, then Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn presented a similar type of threat to elements of Britain’s military-political leadership. In widely reported comments made to The Sunday Times, an unnamed senior military general, who had served in Northern Ireland, warned of mutiny if the leftist gained power.

He was reported as saying members of the armed forces would challenge Corbyn if he was elected into government and attempted to end Britain’s nuclear Trident programme, leave NATO or reduce the size of the armed forces.

Independent leftist candidates, including Corbyn, are now expected to challenge Labour and Conservative politicians for seats across UK constituencies in a General Election to be held before January 2025.

Britain, like other Western nations, faces a period of increasing political tensions, inequality and social discontent.

In a clear sign of such discontent, Workers Party president George Galloway on February 29 won the Rochdale by-election with an enormous majority on a peace and economic justice platform. It prompted British Tory Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to address the nation, called Galloway’s victory “beyond alarming”, claiming he was an extremist and part of “forces now attempting to tear us apart”.

Associating Galloway’s win with protests against genocide in Gaza which he falsely claimed had “descended into intimidation, threats and planned acts of violence”, Sunak further claimed Britain’s democracy was now a target.

Sinister statements such as these, as well as increasingly repressive laws to stifle strikes, protests and dissent, suggest Kitson’s ghost will haunt UK shores in the coming years, justifying fears Britain’s colonial counter-insurgency chickens will one day come home to roost.

The minimal conclusion to be drawn from this investigation is that the British military colluded with terrorists in Northern Ireland. The British state, which routinely categorizes other states as "state sponsors of terrorism", is itself a state sponsor of terrorism.

However it should be equally obvious that British politicians en masse were also colluding with terrorism. This is more stark evidence of the terminal decline of British democracy. Politicians were once expected to be men and women of principle who would provide moral leadership to the nation. The voters then lowered their expectations, hoping only that politicians would be representative of the character and attitudes of the general public. Now we are forced to conclude that they are at best moral imbeciles, complicit in crimes within their own jurisdiction right up to and including premeditated murder.

Mick's article actually holds the clue to how this moral degradation of the Westminster system was set in train. It happened at least in part because the politicians thought they could draw a line between the kind of crimes they condoned in their colonial possessions, and the standards which they claim to adhere to within the home jurisdiction. As any serious student of human character knows, such moral ambivalence is unsustainable.

In this respect, New Zealand politicians are no different to their British overlords. Whether National, Labour, ACT or New Zealand First, they have glossed over, denied and lied about the crimes committed by their military in Palestine, Vietnam, Afghanistan and many over theatres of war. It may be only a matter of time before the colonialist regime is using the same techniques here in Aotearoa.